"To determine our own future, manage our own affairs and become self sufficient so the homeland mala can continue to live in peace and harmony"

Old People’s Vision for the Yolngu of the Homelands

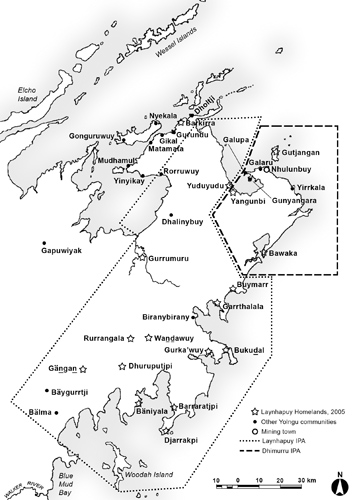

The Yolngu of North-East Arnhem Land have been living with their own law, culture and spirituality for well over 50,000 years. For several thousands years prior to European contact they traded with the Macassans. As early as the 1660's they had a productive relationships with the Dutch around Blue Mud Bay. However, British colonisation of Australia in the 18th century brought dramatic change to Australia's first people and by the 1920's the Yolngu saw the establishment of the first Missions on their land. In the 1930's the Administration of the region was given over to the Church as Yolngu people were forcibly removed from their lands and made to live in Missions towns, such as Yirrkala. The late 1960's saw significant political and social change for the Yolngu and the freedom to move across their lands was re-establishd. In April 1972, partly in response to the establishment of the nearby mining town of Nhulunbuy, senior Aboriginal leaders resolved, with their extended families, to move back to their traditional clan lands and sea country over an extensive area to the south-west, taking charge of their lives, culture and country. This was the birth of the Homeland Movement.

Yolngu speak their own languages and English is usually a 3rd or 4th language. Accordingly English literacy, numeracy and oracy are very variable. Homeland schooling, through a two-way approach of teaching English alongside Yolngu Matha offers a stronger future for the next generation growing up in these communities. Bunggul Djama promotes the maintenance of Culture through a Learning on Country approach.

The majority of Yolngu from the homelands do not wish to be ‘assimilated’ or ‘mainstreamed’. They strongly value their culture and law and links to country, and do not regard the fact of their physical/locational or cultural separateness from the mainstream as equating to being ‘disadvantaged’. They are however, very frustrated, at the failure of government to respect this choice, and to appropriately support their aspirational efforts over the past 30 years for separate development and self-management through the provision of suitable infrastructure and services to develop local capacity.

In recent times indigenous communities across Arnhem Land were subjected to extreme government intervention that dictated community outcomes and deprived the Homeland communities of much needed resources, which were being re-directed into Hub towns, such as Yirrkala. This pushed many of the Elders in the Homeland communities to the edge as it threatened their vision of building a stronger future through Learning on Country. Fortunately, governments and policies change and with the Territory Government’s new Homelands Policy announcement in August 2012, to be co-funded by the Federal government, there is renewed hope that the management and maintenance of existing homeland infrastructure, including houses, roads, and essential services, will finally be resourced. Within this Homeland Policy is scope for the development of business and community projects that can offer training and employment outcomes.

The Laynhapuy homelands are on Aboriginal land held as inalienable freehold title by the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Lands Trust established under the Commonwealth’s Aboriginal Land Rights Act (Northern Territory) 1976. The largest of the homelands has a permanent population of approximately 150 people. Three other homelands have a population of 70-100 people, and several with 40-70 people. These homelands are based up to 290 km from Yirrkala and are spread across an area of some10,000 km2 including one off shore island.

The homelands include:

| Balma | Bunhanura | Galkila | Raymingirr |

| Barraratjpi | Burrum | Gangan | Rurrangala |

| Barrkira | Buymarr | Garrthalala | Wandawuy |

| Bawaka | Dhalinybuy | Gurrkawuy | Yalakun |

| Baygurrtji | Dhuruputjpi | Gurrumuru | Yangunbi |

| Bukudal | Djarrakpi | Gutjangan | Yilpara |

| Donydji | Mirrngatja | Yuduyudu |

These homelands have a collective population of up to 1,000 residents during the dry season and about 700-800 during the wet. The Dry season is a time set aside for larger cermonies requiring partcipation from a number of clans who travel considerable distances to attend. During these occasions it's not unusual for the small communities to play host to a transitory population 10-fold normal capacity.

Given the geographical isolation of the homelands, services can be expensive and marginalised. As oft quoted amongst our team, $1500 from Nhulunbuy to Gapuiwiyak via a Bush Taxi is what we call, exorbitent. Yet, despite the expense, each week several families wil pool together and take the bush taxi out to the community in order to get the children and shopping back home from Nhulunbuy, where all major services are centred in the North-East region.

Despite the hardships associated with living in remote communities, the reality is that the isolation of the homeland communities is also their greatest strength, as it helps to keep the culture strong and this is the pathway BJAA is following; the strengthening of communities by diversifying and broadening the educational and employment base for youth wthin the homelands.